Modes of interview, such as face to face, web and telephone, are an essential dimension of any survey data collection. The decision of which mode to use will impact everything from the sample frame used to the incentives, timescales and the design of the questionnaire. There has been a steady move away from traditional modes of interview (i.e., face to face and telephone) to web or mixed mode designs (where multiple modes of data collection are used). The latter is especially attractive as it can potentially save costs while retaining higher response rates.

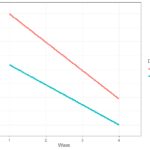

That being said, moving a study to a mixed mode design can be challenging. This is especially true for longitudinal studies where comparisons in time are essential. By introducing new modes of interviews in longitudinal surveys estimates of change could be potentially biased as respondents might be susceptible to different types of measurement error depending on the mode of interview used.

In order to understand the potential impact of the mode of interview on estimates of change it is essential to understand how people could switch from one mode to another. If people always answer in the same mode then the potential bias due to the mode of interview is relatively small. On the other hand, if respondents often switch modes of interview it could potential lead to an artificial increase in the estimates of change.

Exploring mode switching using latent class analysis

In a recent study we have investigated exactly this question. More specifically we looked at how respondents switch modes in a longitudinal mixed mode survey and what individual level characteristics are associated with this process.

We used the Understanding Society Innovation Panel which has an experimental design in waves 5 to 10. More precisely we used a random sub-sample that had collected data using a sequential web-face to face design (i.e., people were first invited to participate by web and if they were non-respondents they were invited to a face to face interview).

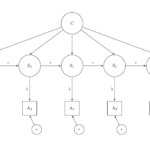

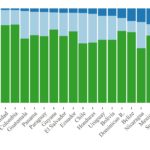

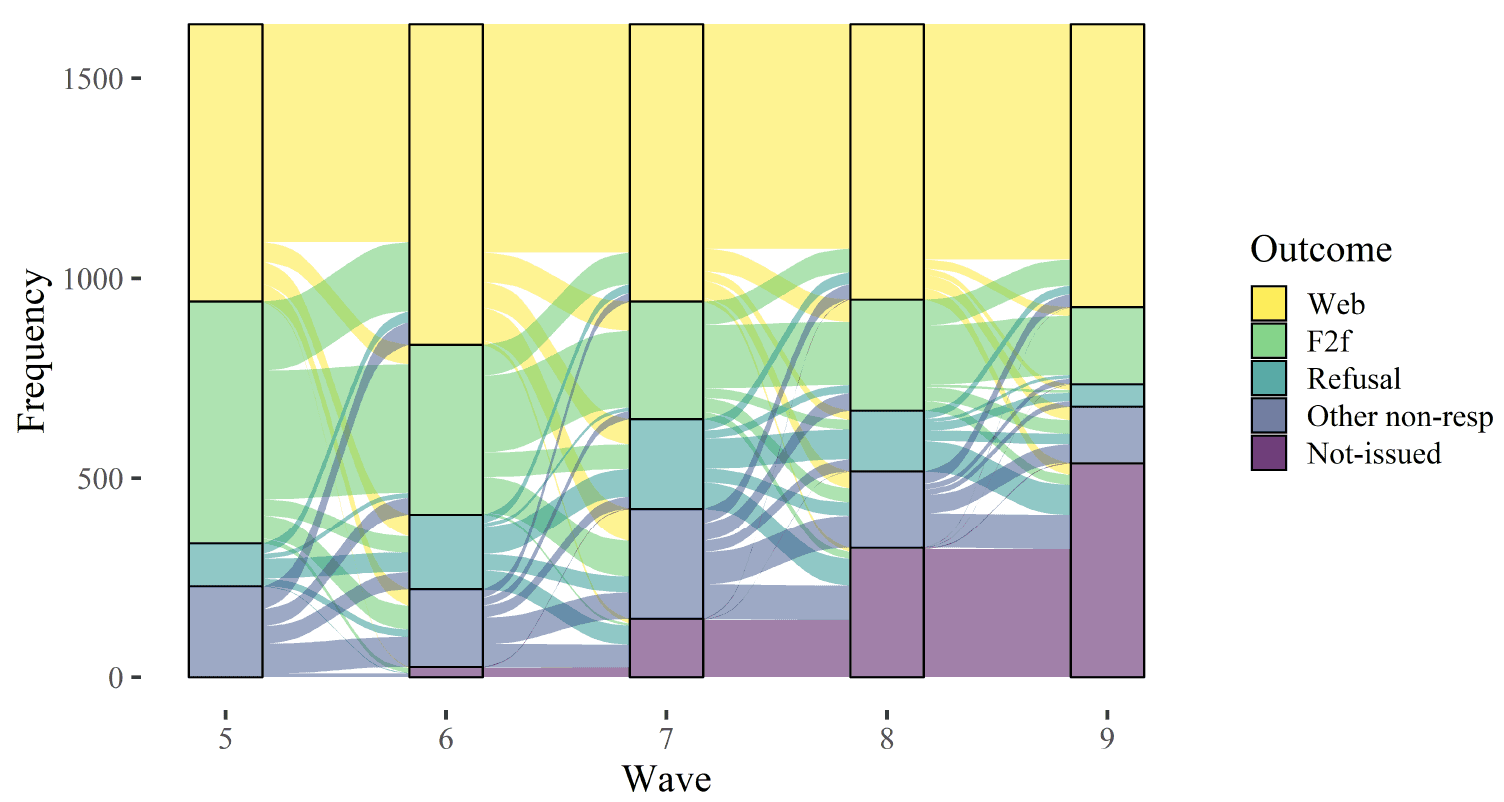

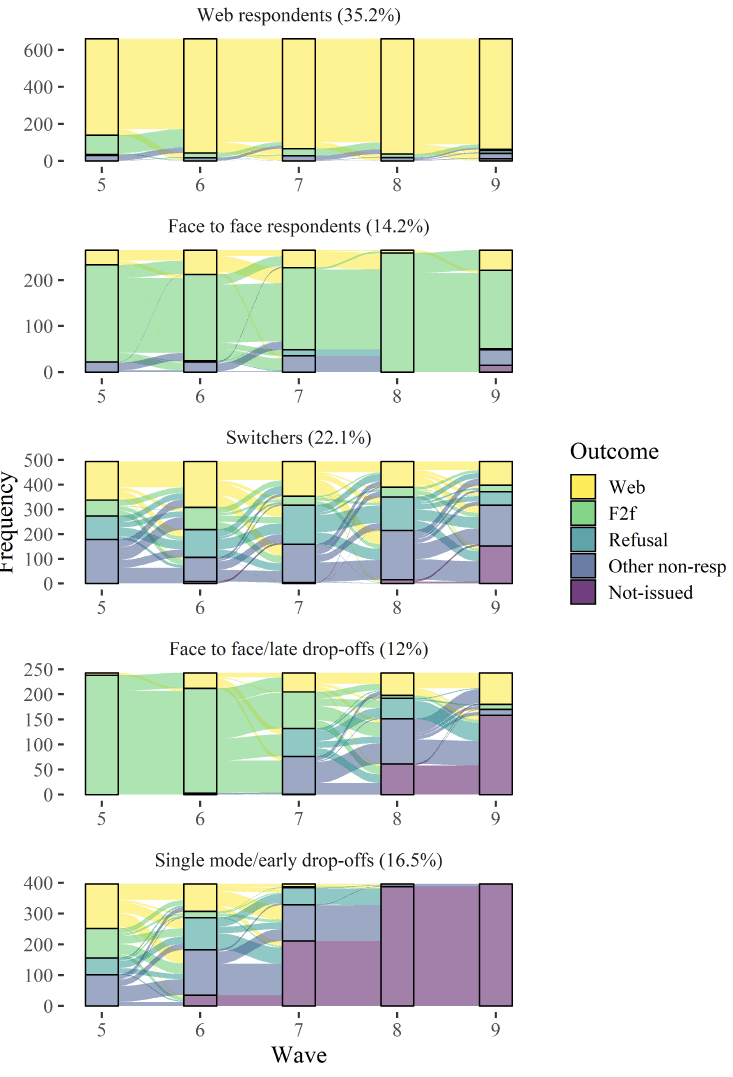

We used this data to run a series of latent class models to identify groups of respondents based on their patterns of change. We identified five groups (which you can see in the graph below). The first two groups include those respondents that are likely to always participate in the same mode. Stable web respondents represent around 35% of the sample while stable face to face respondents represent approximately 14% of the sample. We also identified three classes of people that often switch modes. The “switchers” represent 22% of the sample and show the highest level of transitions between the modes of interview throughout the study. The “face to face/late drop-offs” tend to participate by face to face in waves 5 and 6 and then to drop off. Finally, the “single mode/early drop-offs” tend to stop participating after wave 5.

To better understand these groups, we estimated a series of models using individual characteristics to explain the likelihood of belonging to each class. We found that when compared against the “Face-to-face respondents”, respondents who were partnered, highly educated, tech savvy, and indicated they prefer the web mode were more likely to belong to the “Web respondents” class. Respondents with A level education, missing data on a question about internet use, and those who preferred the web or mail survey modes were more likely to belong to the “Switchers” class, whereas older people and those who volunteered were less likely to be in the “Switchers” class (in favour of the “Face-to face respondents” class). Older respondents and those who received many telephone contact attempts in wave 4 were more likely to belong to the “Single mode/early drop-offs” class and “Face to face/late drop-offs” class, respectively, as opposed to the “Face-to-face respondents” reference class.

Finally, we explored the potential of using these classes to predict future outcomes in the study, such as participation and mode of interview. We found that the classes can help improve prediction accuracy compared to models that include only respondent characteristics and outcomes at the last wave.

Conclusions

While the use of mixed mode designs has become standard in modern data collection our understanding on how this can impact estimates of change is still lagging behind. A key aspect to understanding the potential bias due to switching modes in a longitudinal study is to actually understand who are the people that change modes of interview and how often they do it. This works shows how we can explore these patterns of mode switching using latent class models. We see that roughly half of the sample tends to change modes of interview. Based on these results these groups could be potentially targeted to minimize mode switching and increase participation in future waves.

You can find out more about this research by checking our peer-reviewed article.