With the increasing availability of new forms of data new ways of collaborating and teaching need to be developed. Here to talk about these topics is Professor Florian Keusch, a leading expert in this field.

Florian is a Professor of Statistics and Methodology (interim) in the Department of Sociology at the University of Mannheim and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Joint Program in Survey Methodology (JPSM) at the University of Maryland. At the University of Mannheim, he is also affiliated with the Mannheim Centre for European Social Research (MZES) and the Collaborative Research Center SFB884 “Political Economy of Reforms”.

Find out more about Florian on his website: floriankeusch.weebly.com

Can you say a little how you started doing research in survey methodology?

I guess like many others in this field, I did not know that I would end up doing survey methods research when I started studying at the university. After high school, I wanted to get into sports management or sports marketing but since there was no specific program for that in Austria at that time, I decided to study business administration at WU, Vienna University of Business and Economics. Through courses in marketing, I learned about marketing research, and I was really intrigued by what it takes to measure peoples’ attitudes and behaviors with surveys.

After graduating with a Master’s degree in business, I decided to do a PhD in Social and Economic Sciences at WU because I wanted to learn more about the different methods used in social science research, and I really liked the academic environment in general. I was lucky to find an advisor who encouraged me to study web survey methods in my dissertation thesis, a method that was still quite new and controversial in the mid-2000s, at least in Austria. While others in my program attended marketing science conferences, I went to AAPOR, ESRA, and GOR, and I loved the methodological work that people presented there. I tried to build as many personal connections to the survey methods world as possible and luckily enough, I was offered a post-doc position at ISR in Michigan after I graduated with my PhD. This opened up a ton of doors for collaborations with like-minded people to do more research on data collection methods.

What are your main interests in this field and why?

My research revolves around the evaluation of innovative data collection methods. Most recently, this involves the combination of self-reports through Web and mobile Web surveys with new forms of “organic” data, for example, sensor data from smartphones and wearables or Internet search data. In my research, I primarily assess the methodology of these new forms of data collection, what are the errors associated with collecting data a certain way. However, I am also interested in studying the feasibility of using these new forms of data collection to answer specific substantive research questions. I think this is a particularly exciting aspect of my research.

I really enjoy working with researchers who have a substantive research focus and I try to help them use these new technologies to collect data to better study a specific phenomenon they are interested in. A good example of this type of research is our IAB-SMART study where we developed an app that passively collected sensor and log data from members of an existing longitudinal survey (PASS) in Germany. We did extensive methodological work on coverage, nonparticipation, and measurement error in this project to better understand the quality of the data that comes from the smartphone sensors and logs, and we are no working with labor market sociologists and work psychologists to answer substantive questions, for example, on the influence of unemployment on social inclusion and smartphone induced-stress at work.

General Online Research conference

In the last years you have been involved in the organization of the General Online Research conference. Can you say a few things about the conference and the organization?

The General Online Research (GOR) conference is annually organized by the German Society for Online Research (DGOF) and brings together around 350 international researchers from different sub-fields in academia (sociology, psychology, political science, economics, market and opinion research, data science) and the industry who study and use online research methods. What I really like about the conference is that it is a great place for people from both worlds – academia and the industry – to present state-of-the-art methodological and applied work and exchange their experiences. There is a strong community feeling at the conference and many people come back every year because they appreciate the interdisciplinary flavor combined with the academic rigor of the peer review – which is both done by academics and people from the industry. At the same time, the atmosphere at the conference is very friendly and supportive, so it is a great conference for young researchers to present their work for the first time.

Officially, I have been involved in the organization of GOR since 2018, when I became the Vice Programme Chair, and I am right now also in charge of Track B – Data Science: From Big Data to Smart Data. However, I have been attending GOR since 2007, and it was also at GOR that I gave my first presentation.

How did the themes and the research change in the period?

While the overall theme of the conference has always been around state-of-the-art methods in online research, the particular methods that are presented and discussed at the conference have certainly changed over the past 13 years, since I first attended.

Right now, there is, of course, a lot of interest in new forms of “found”, “organic”, or “smart” data that come from other sources than designed surveys and experiments.

Originally, the focus was exclusively on web surveys as a new method of survey data collection. While there is still a large number of presentations on web survey methods and as an extension now also on mobile web surveys, new themes were added (and dropped again) over time. Right now, there is, of course, a lot of interest in new forms of “found”, “organic”, or “smart” data that come from other sources than designed surveys and experiments. We have sessions on social media research, combining surveys with sensor and digital trace data, and how to use machine learning to work with unstructured data.

Over the last couple of years, we have added a track with a more substantive focuses on Politics, Public Opinion, and Communication to the conference. This addition reflects high degree of methodological innovation in this field.

Another aspect of the conference that has certainly changed over time is that GOR has become much more international. Originally, GOR stood for German Online Research, but now it truly is an international conference with participants coming from around the globe.

Can you share a few things that you have learned from running and attending this conference?

Compared to other conferences such as AAPOR, ESRA, and JSM, GOR is relatively small with around 350 participants. However, even at that size it would not be possible to pull this off if we didn’t have a large team working together in the background year-round. I think as an outsider, you do not see all that it takes to run a conference, and that’s definitely something I needed to learn to appreciate.

We have a fairly large programme committee with two chairs for each of our tracks, one each from academia and one from the industry, who are in charge of distributing the call in their respective communities, recruiting reviewers, and eventually putting together a program. Others are in charge of organizing the pre-conference workshops and judging various competitions, such as the Thesis Award, the Poster Award, and the Best Practice Award. People on the programme committee don’t have fixed terms and some of us have been doing this for a couple of years now, but then we also try to have people rotating in and out over time to make sure that there is room for new ideas and innovation.

While the work on the programme committee is volunteered, we also receive absolutely incredible support from DGOF staff who basically do all the logistics works, including negotiating contracts with local hosts and caterers, finding sponsors, administering the conference ticketing system, and so many other things that make our lives as programme chairs so much easier. Seeing what it takes to make a conference run smoothly, makes me look at other conferences from a totally different perspective.

Mobile Apps and Sensors in Surveys (MASS) Workshop

Recently you also organized the Mobile Apps and Sensors in Surveys (MASS) Workshop. Why did you feel a new workshop was needed?

The idea of the MASS workshop is to bring together researchers from different disciplines to discuss the current state of their work on the use of mobile apps, sensors, and log files in survey data collection.

Sensors built into smartphones and wearables are increasingly used in social science research. We just finished a large study in Germany – IAB-SMART – using an app that collected smartphone sensor and log file data and administered survey questions to participants to study social inclusion and labor market activity. Others in Europe and the U.S. have been using similar technology to study expenditure, mobility, physical activity, mood, and other phenomena.

A lot of this work still seems to happen in small pockets in different areas of research, and when talking to colleagues who were engaged in these projects, many confirmed that we needed a platform to share our experience and discuss the methodology further. That’s when Bella Struminskaya and Peter Lugtig, both from Utrecht University, and Jan Karem Höhne and I in Mannheim decided to organize a workshop. The first one was held in 2019 in Mannheim, and around 40 people attended.

We recruited many of the attendees from our personal networks in the survey methods world but we also had participants with a more technical background in app development and, for example, from psychology and public health.

I strongly believe that the core strength of data from sensors and apps lies in their combination with self-reports and sample surveys.

The workshop went really great and as a follow-up, a special issue on this topic is coming out soon in Social Science Computer Review. The next MASS workshop will be held in Utrecht in 2021.

What are the opportunities for survey methodology in this area?

I strongly believe that the core strength of data from sensors and apps lies in their combination with self-reports and sample surveys. Data collected through sensors and apps have many of the characteristics of what is now called Big Data; they come in a number of often less structured formats (e.g., accelerometer readings, GPS coordinates, app use time stamps); they can be collected at extremely high frequency, virtually constantly; and data collection is nonreactive because it happens passively in the background on a device.

Incorporating this new form of data collection into probability surveys allows researchers much more control over the data collection process.

While this provides extremely interesting and relevant data for many social science researchers, the issue with these “found” data usually is that they come from volunteers who have self-recruited into downloading a specific app or using a certain device, and we don’t know much, if anything, about the users. Incorporating this new form of data collection into probability surveys allows researchers much more control over the data collection process, for example, by recruiting probability samples of a well-defined population and potentially even providing the technology to those who do not have access yet.

In addition, the researcher can specify what sensor is used and at what frequency the data are collected. Self-reports add valuable context to the sensor data (e.g., self-reporting the purpose of a trip that was passively detected) and provide relevant background information about the participants, which can then be used as covariates in the analytical models. We like to think about this as “bringing design to Big Data”, combining the strength of both worlds.

What are the main challenges in this area?

I see two major challenges here. First, nonparticipation and noncompliance in studies collecting sensor data is a concern. While we can, at least in theory, overcome problems of undercoverage by handing out devices to study participants who do not own the technology, we see that participation rates are relatively low. Even in studies that recruit participants from existing longitudinal surveys, where we would expect relatively high trust in the data collection organization because there is an established relationship, installation rates for apps that passively collect data on the smartphone are usually lower than 20%.

We have studied reasons for nonparticipation, and the major driver seems to be concerns about privacy and data security. This is not surprising given that some of the information collected is very sensitive. I think as researchers, we need to do a better job in explaining to potential participants what it is that we are doing and how we handle and protect their data to increase trust.

We have studied reasons for nonparticipation, and the major driver seems to be concerns about privacy and data security.

The second challenge is that we still need much more research that helps us understand the quality of the new data. One could naively assume that sensor data are error-free but nothing could be further from the truth. The quality of the sensors built into smartphones and other devices vary sometimes dramatically, and what and how much data are eventually collected can be influenced by many factors (e.g., battery level, system settings, operating system, device handling by the user) that are outside of the control of the researcher. We need to better understand for what phenomena and under what circumstances sensor data are in fact the better measures and when we should still rely on self-report data.

Mannheim Master of Applied Data Science & Measurement

(formerly IPSDS)

Yet another project you were involved with is the Mannheim Master of Applied Data Science & Measurement. Can you say a few things about the program? What makes it different to other programs?

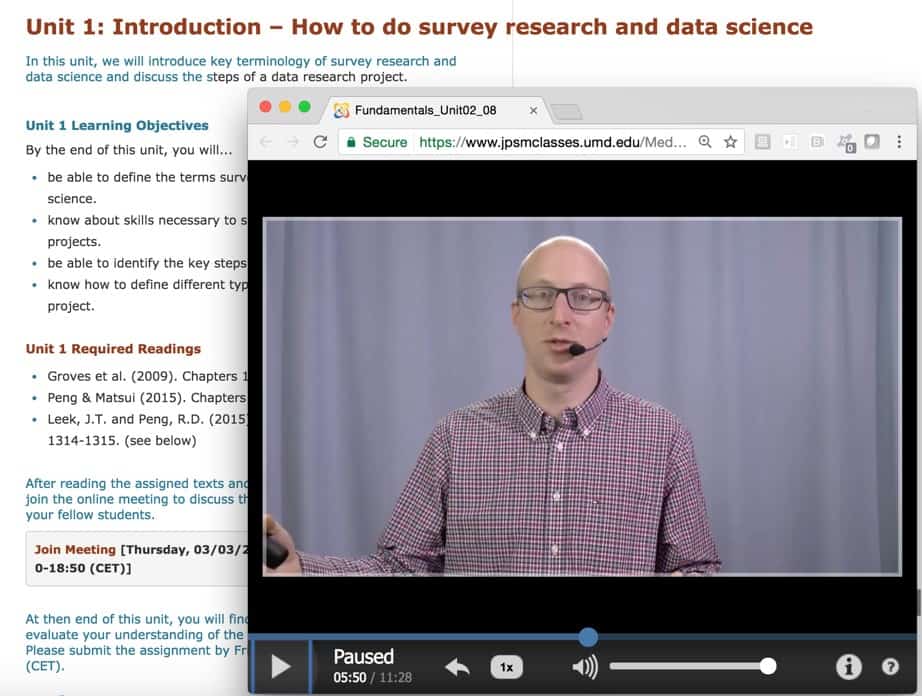

The International Program in Survey and Data Science (IPSDS – now called Mannheim Master of Applied Data Science & Measurement) is an online Master’s degree program for working professionals in the areas of opinion, market, and social surveys as well as employees of survey research enterprises, ministries, and statistical agencies worldwide, or more broadly speaking any organization that works with data.

IPSDS adds to these key areas expertise in data collection and data quality given various types of data as well as their combination to answer specific research questions.

The program was initially funded by a grant from the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research to Frauke Kreuter, and it is administered jointly by the University of Mannheim and the Joint Program in Survey Methodology at the University of Maryland. We currently have students enrolled from all continents.

What makes the program different from other programs is two things. First, while most data science programs focus their curricula entirely on the technical aspects of the field, that is, statistics and/or computer science, IPSDS adds to these key areas expertise in data collection and data quality given various types of data as well as their combination to answer specific research questions.

Second, although the program is fully administered online, IPSDS courses are not run as MOOCs where thousands of people take the same course at the same time but never interact with each other nor with the instructors. Our courses are set up in small groups of a maximum of 15 people, and we use a flipped classroom design. For every unit in a course, students get assigned video lectures, readings, and small exercises or projects that they can work on in their own time. Usually once a week there is a live-video meeting with the instructor and the entire class where the materials are discussed or some exercises are done.

In addition, once a year, we have an event in Mannheim that all our students are invited to attend in person with additional workshops and guest lectures. This set-up fosters collaboration between students and allows them to expand their personal and professional network.

What are the new skills that the new generation of survey methodologist need?

We see that even in organizations that still heavily rely on “traditional” survey data collection, alternative and new data sources are increasingly being used, this includes, for example, digital trace data from Internet users’ online activities, social media posts, geolocation information and sensor readings from wearables, satellite images, and administrative records. These data are either used as substitutes for surveys or, more and more so, in combination with survey data.

Handling, storage, and analysis of such data sets require new skills that survey methodologists were traditionally not trained, so courses on natural language processing, topic modeling, machine learning, data base management, and data visualization are very popular right now.

Other than surveys that are designed by a researcher to answer a specific question in mind, these new data are often a by-product of existing processes. To work with these data you will need to understand how they were generated, how they can be accessed (e.g., through web scraping or using APIs), and how they can be linked.

While survey data usually come in a straightforward format (rows in a data set represent respondents and columns the variables), many of the new data are rather unstructured and the data sets can become extremely large quite fast. Handling, storage, and analysis of such data sets require new skills that survey methodologists were traditionally not trained, so courses on natural language processing, topic modeling, machine learning, data base management, and data visualization are very popular right now.

This does not mean that all survey methodologist need to become programmers, Machine Learning experts, or IT infrastructure specialists. However, a basic understanding of how one can work with these data will be essential when collaborating and communicating with specialists in multi-disciplinary teams.

What do you think could the contribution of survey methodology to the field of data science?

The fact that more and more organizations work with non-survey data does not mean that surveys and survey methodologists will become obsolete, quite the opposite. In fact, the number of surveys conducted worldwide is steadily increasing, and even organizations that are heavily relying on non-survey data have by now figured out that they need information that can best be collected through self-reports; especially opinions, attitudes, and other information that provide context to behavioral data.

I would say that the focus on data quality that survey methodologists bring to the table are exactly what’s needed in these positions.

For example, organization such as Facebook and Google have lately hired lots of people with backgrounds in sampling, questionnaire development, and research design. Often these jobs are not called survey methodologists any more – I have seen the labels UX researcher and quantitative social research – but in general, I would say that the focus on data quality that survey methodologists bring to the table are exactly what’s needed in these positions.

Finally, what do you think are the most important challenges in our field in the coming period?

Since we now often have access to data from multiple sources, we will need to better understand which data are better suited for what purpose under what circumstances, and how to use the data from multiple sources jointly to better answer specific research questions.

Another issue that I see is that high costs and low response rates of probability-based sample surveys have led to an increased use of nonprobability samples. While there is a well-established statistical theory that allows us to produce population estimates from probability samples, we still do not know when it is appropriate to generalize from non-probability samples to a population.

As long as we do not have a better handle on this issue, we need to educate users of non-probability samples that there are severe limitations to their use.

Find out more about Florian on his website: floriankeusch.weebly.com/